Patriarch of Pandemics

In the last article we covered some of the historical pandemics that rocked the world - smallpox, typhoid, and the bubonic plague. We ended on a hopeful note - many of the pandemics that plagued the world in the past have faded, and that modern pandemics have been far less fatal than historical ones.

In this article we’ll dive into one big pandemic of the 20th century - influenza. The next article in the series is going to start in on the coronavirus pandemics of the last few decades, and then we’ll end with an in-depth analysis of what’s going on with COVID-19.

A century of little victories

Since the discovery of antiviral and antibiotic medicines, human existence on earth has gotten a lot easier. While access to medicine has not always been ideal, we’ve made amazing steps towards improving human quality of life by decreasing disease. Through concerted vaccination programs, we’ve eradicated smallpox and closed in on the poliovirus. We’ve nurtured a global organization, the World Health Organization, whose mission is the attainment of health for all humans. They’re the ones that monitor endemic and epidemic diseases and come up with a coordinated effort that’s capable of halting the spread of disease. The WHO has been around since the 1940s, and new technologies have seriously improved their ability to evaluate how diseases spread. Monitoring is so good at this point that it’s possible to sit on the internet in Dubuque, Iowa or the Kalahari desert and track the development of COVID-19 in real time.

In addition to information technology, there’s also been an explosion of molecular techniques that allow us to better identify what we’re dealing with. Sequencing, protein crystallization, high throughput mechanism studies all happen quickly enough to make your head spin. The global response to the pandemic, barring some political hiccups, has been amazing. It becomes even more astounding when you compare the fallout from COVID-19 with something like the 1918 influenza pandemic.

A simpler time

Let’s set the scene a little. It’s January 1918. The war has been going since the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand in 1914, and something like 3.5% of the world’s population has been mobilized to the front. The front is crowded, cold, and dangerous. Soldiers are dying of prosaic illnesses - tuberculosis, typhoid, trench foot. They spend months at a time in open trenches filled with human and animal waste. The war is largely at a detente, with few real gains or losses. Except, that is, for loss of life. New weapons like tanks and flamethrowers increase the lethality of combat. Chlorine gas, it’s ubiquity a side-effect of burgeoning industrialization, is used for the first time as a weapon. War is hell, and these soldiers, besieged by a new generation of tools of destruction, regularly confront the possibility that the world might actually be ending.

Science can explain how things happen, but poetry is a much more effective at explaining how things feel. I leave it to Wilfred Owen, the ill-fated poet who died just months before the armistice was signed in November of 1918, to describe the utter horror in his poem, Dulce et Decorum Est.

Bent double, like old beggars under sacks,

Knock-kneed, coughing like hags, we cursed through sludge,

Till on the haunting flares we turned our backs,

And towards our distant rest began to trudge.

Men marched asleep. Many had lost their boots,

But limped on, blood-shod. All went lame; all blind;

Drunk with fatigue; deaf even to the hoots

Of gas-shells dropping softly behind.

Gas! GAS! Quick, boys!—An ecstasy of fumbling

Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time,

But someone still was yelling out and stumbling

And flound’ring like a man in fire or lime.—

Dim through the misty panes and thick green light,

As under a green sea, I saw him drowning.

In all my dreams before my helpless sight,

He plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning.

If in some smothering dreams, you too could pace

Behind the wagon that we flung him in,

And watch the white eyes writhing in his face,

His hanging face, like a devil’s sick of sin;

If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood

Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs,

Obscene as cancer, bitter as the cud

Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues,—

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old Lie: Dulce et decorum est

Pro patria mori.

It’s in this world that a new sort of flu appears. It’s more virulent and deadly than any that has come around in human memory. The first cases are reported simultaneously in multiple locations. There’s some in France, England, the US. They’re reported as medical curiosities by doctors in the field - blood in the sputum, purulent bronchitis, dusky heliotrope cyanosis - the side effect of a patient drowning in their own lungs.

Because the war is still going, and casualties are higher than they’ve ever been in another armed conflict, there’s no time for these doctors to institute reasonable quarantine measures. Those that are so sick they can’t keep on their feet are in the field hospital - everyone else? They’re out in the trenches, quietly spreading the infection. Troop movements, an overall lack of sanitation, a lack of consideration for a more lethal version of a common ailment all contributed to the wildfire spread of the virus. Over the course of the next year, more people would be dead of the flu than died in the Great War.

How does a virus appear out of nowhere?

The frustrating answer is that we can’t really say. The war consumed attention resources to such a degree that tracing the origins of the pandemic. Combine that with a lack of data on viruses that preceded the 1918 flu, and you’ve got a perfect mystery on your hands.

Our best bet at understanding what happened leading up to the 1918 pandemic comes by way of reconstructions from original data sources. Historians, including J.R. Oxford, cited above, have looked at medical records from the WWI front, and have identified ‘herald waves’ of the virus.

Herald waves are like small eruptions before the big show - usually more deadly than the subsequent pandemic.

They’re more deadly because the virus is new, and people exposed to it have no immunity yet. The virus has managed to find a new host, but still needs to fine tune it’s lethality in order to spread like wildfire. Too harsh of an infection is costly to reproductive fitness, as your host will die before you can be distributed through the community.

As we’ve seen with recent coronavirus pandemics, animals can be viral reservoirs. Under the right conditions, these species-specific infections can mutate in such a way that promotes survival, replication, and transmission inside of a human host. Soldiers at the front were living in exactly the kind of conditions that promote intra-species transmission.

Trenches at the front were often filled with a wet sludge - high water tables would flood them as they were dug, and the muck inevitably filled up with a foul combination of human and animal waste. Since frequent handwashing was inaccessible, transmission of the virus across species lines was almost inevitable, given the oro-fecal transmission of swine and avian influenzas. Another version of events has the virus spreading outward from China, starting the fall of 1917.

The reality is, we can’t pinpoint the origin as well as we can today. What we do know is that influenza infections were widespread by summer of 1918.

The Flu Stalks its Prey

Once the virus had spread through the trenches, it was only a matter of time before it reached the general population. Soldiers, on average, had eight month deployments before being sent on furlough. Those that were healthy enough to be in the trenches were given leave, and they scattered the viral seeds as they went.

The pandemic spread through the global population in three waves (an explanation for the cyclic nature of the flu warrants revisiting in a later article…). The first wave washed across the world in June/July of 1918, and killed about 5/1,000, which gives a total fatality rate of 0.5%. The second wave was the voraciously deadly one - 2.5% of the population died. In certain places, the impact was much worse. Over the course of five days, 72 of 80 Inuit adults died in Brevig Mission, AK. In Philadelphia, 1,000 people a day were dying at the peak of the pandemic.

It’s during this second phase of the pandemic that a strange feature of lethality emerges, one for which there still isn’t a clear explanation. Normally, the majority of flu deaths come from people over the age of 65 and below the age of 1. This gives a U-shaped mortality curve where the people in middle age show the lowest mortality rate. But the 1918 flu was different - it showed a characteristic W-shaped mortality curve. In the fall of 1918, patients between the ages of 25 and 35 were the likeliest to succumb.

Mortality from 1918 Influenza in red, compared to overall mortality from pneumonia in the UK between 1911 and 1918. Notice the peak centered around 30 years of age for the 1918 flu. Image source

On November 11, 1918, the armistice between the Allies and Germany was signed. With it, the war was over. Troops remained on the front, waiting on Germany to leave first. The deadly flu season peaked with the ceremonial end to armed conflict. Mortality declined steadily through February of 1919, rising again for a brief moment. Then, as if it had never been, the pandemic was over. The Great War destroyed the stability of a generation, and took 20 million lives. The 1918 pandemic, without a single bullet, would take 40 million.

What makes a virus deadly?

There are different opinions on the matter. Some have proposed that those older than 65 could have been previously exposed to a similar virus that left behind a certain level of immune protection. Others have suggested that those in middle age simply bore more of the weight of war. Malnutrition, stress, despair - all could have played their part in boosting the death toll.

For a long time, speculation was the best way of telling the story of the virus - no sample had been successfully extracted that contained all of the DNA. This changed in the 1990s, when fragments of the viral genome were successfully isolated from two places: a lung sample taken from a soldier, and from a body buried in the permafrost in Brevig Mission, AK.

Scientists have been asking why the disease was so deadly since the 1930s when a virus was identified as being responsible for influenza, but had precious little data to work with. The viral cycle of the flu means that a patient is only shedding viruses for five to six days post infection. Since most patients died after that point, samples gathered from them contained no viral particles.

Dr. John Hultin had read about the tremendous death toll in Brevig Mission, and had seen something no one else had - the bodies of the dead, buried as they were in a mass grave in the Alaskan permafrost, might carry preserved viral particles. He attempted an expedition in the 50s, and came back empty handed. Hearing about the CDC team that was attempting to reconstruct the virus, he decided to make another attempt. 46 years after his first attempt, he received permission from village elders to try again. This time, he found viable lung tissue, and sent it along to the team at the CDC.

"The virus sat and waited for me," he says. "Maybe it was good I -didn't find it before, technology -wasn't ready for it yet. Also, if I had found it, I would have become a famous person, my future would have been very narrow. I - didn't find it, so I had the chance to do other things.”

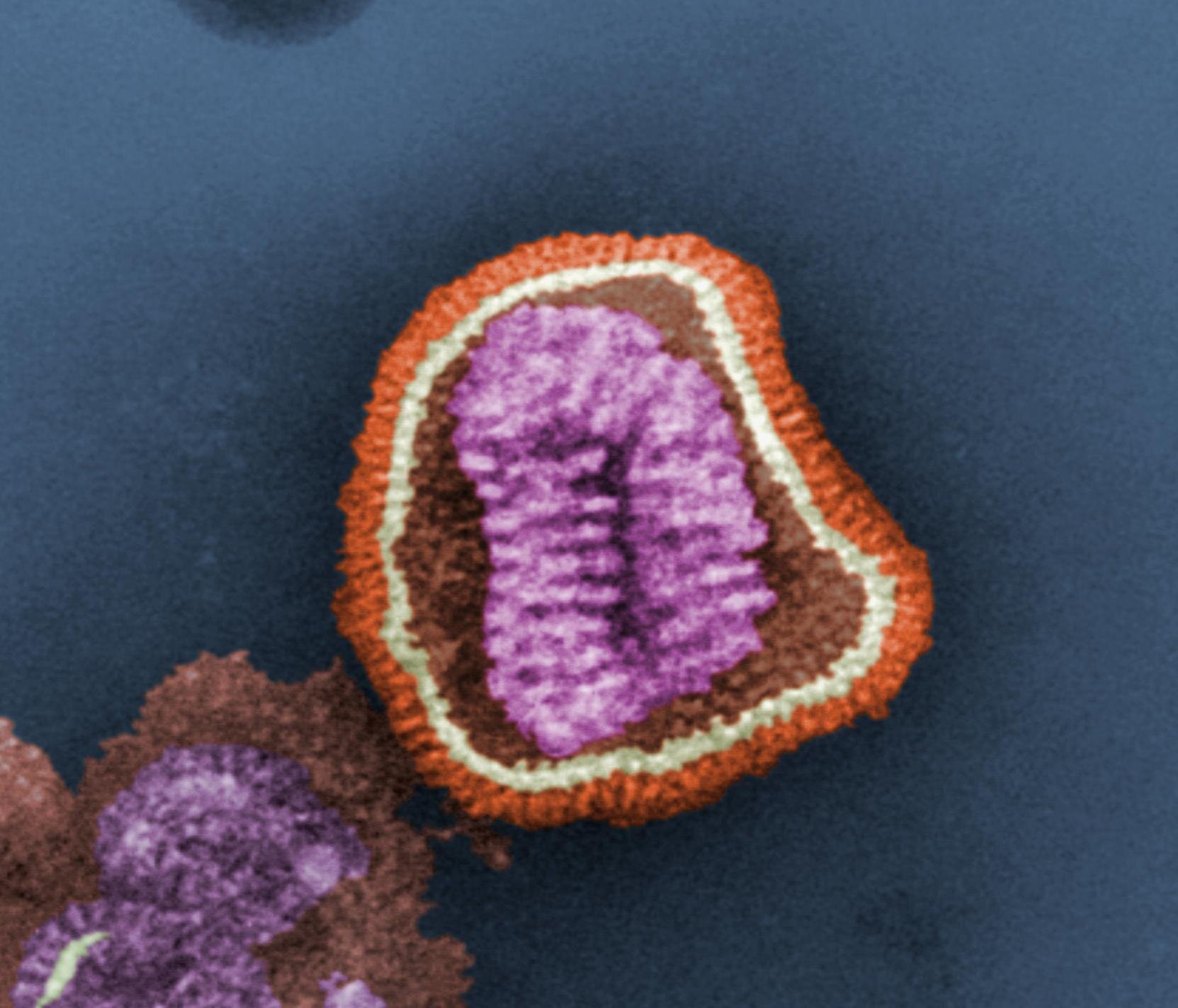

A false-color image of the flu virus from the CDC. DNA on the inside is purple, matrix proteins are in white, coat proteins in orange. Image source

The CDC sequenced the available samples and managed to reconstruct the genetic information of the entire virus. Working in a highly secure laboratory in the bowels of the CDC, the team managed to revive the virus from synthetic genetic material. With the functional virus in hand, they were able to test how the various viral features - envelope proteins, matrix proteins, biochemical ability, contributed to its astounding virulence.

What they found was surprising. There wasn’t any one feature that made the virus so dangerous. It was just a series of unhappy accidents that so many variables had combined to form a real pain-in-the-ass for most human immune systems. The same team also attempted to answer the question of where the virus came from in the first place, and reported another bombshell. Usually, viruses like the influenza virus can be categorized by the species they have co-evolved with. There’s swine flu, bird flu, even horse flu. The 1918 virus, though, seemed like a chimera. Parts of it had come from birds, others from pigs or humans. A group from Shandong University published a paper in 2019 furthering the case for a chimeric virus - one that was a product of human and avian viruses.

Viral recombination is like a Mr. Potato head of biology. Infect a single host with multiple viral strains that reproduce in the same cells, and they’ll spontaneously reassemble into new kinds of viruses. An eye from here, a nose from there, lips from there, and all the sudden it’s a new virus.

This is because there isn’t really a master plan that regulates viral assembly in the host cell - the pieces that are manufactured by host machinery fall together because of protein folding dynamics and surface properties. If there’s multiple types of compatible parts around, the end result is a novel virus.

The Patriarch of Pandemics?

Given the lethality of the original 1918 flu, it’s obvious that you would want to steer clear of the thing at all costs. The pandemic swept across the world in three phases, killed 40 million people, and then what? Did it just vanish into thin air, dominated by the superior immune systems of the survivors?

Yes and no. The same group that reconstructed the 1918 virus pointed out that the orignal virus never really disappeared. In a 2006 paper in the Emerging Infectious Diseases Journal, the authors make the following claim:

“All influenza A pandemics since that time, and indeed almost all cases of influenza A worldwide (excepting human infections from avian viruses such as H5N1 and H7N7), have been caused by descendants of the 1918 virus, including "drifted" H1N1 viruses and reassorted H2N2 and H3N2 viruses. The latter are composed of key genes from the 1918 virus, updated by subsequently incorporated avian influenza genes that code for novel surface proteins, making the 1918 virus indeed the "mother" of all pandemics.”

There’s a lot a abbreviations there, so I’ll forgive you if you’re lost for a second. H and N in H1N1 refer to the proteins on the outer surface of the virus. H stands for hemagglutinin, and is responsible for the virus’ ability to glom onto its target cell. N refers to neuroaminidase, the protein responsible for releasing completed viruses from the surface of the infected cell. Further reading on the topic here, summary of how 1918 flu is related to seasonal flu here. Subtypes of the virus are characterized by these two proteins. What the above paragraph is saying, is that the spanish flu didn’t go anywhere. It’s still around us, every year. A recombined version of it reared its head in 2009 as Swine Flu . Another case of recombination leading to the appearance of more deadly viruses.

The virus that killed 40 million circulates in a related form today as seasonal flu - a dangerous but tolerable seasonal illness. The death toll from the 1918 virus was a perfect storm, and underlines that a novel virus is always more deadly than subsequent generations. The human immune system, when functional, is an amazing defence against a previously encountered illness. This ability is the technical basis for vaccines, and the reason for ancestral resistance to something like smallpox in Europe. The same virus, slightly mutated from it’s 1918 self, is simply less dangerous to a population with trained immune systems.

The Takeaway

The 1918 pandemic, deadly as it was, is still around today in the form of a mutated seasonal flu. Following global exposure and culling of the most vulnerable populations - middle aged adults that were most affected by the negative effects of the war - the lethality of the virus is significantly less.

Zoonotic viruses, ones that propagate in species that live alongside but are not humans, are here to stay. Close contact between humans and animals can lead to viral transmission, and reciprocal exchange of the virus across species lines can suddenly produce much more lethal versions.

I’m left with some questions that I’ll do my best to answer in later articles. How closely related are the seasonal flus to the original 1918 virus? How much of our immunity has to do with ancestral exposure?

In the next article in the series we’re going to start in on the coronaviruses - a new family of zoonotic viruses that’s on everyone’s mind.