Urban Growth, Social Death

Since COVID-related social restrictions have swept the world, there has been widespread speculation on the effect that lockdowns will have on our mental health - especially as they extend from weeks into months. One pressing concern was that sheltering-in-place with a romantic partner would lead to another baby boom, reversing decades of birth control advocacy as lightly as the reusable bag ban reversed decades of efforts to control single-use plastics.

Luckily, a group of sex researchers from the Kinsey Institute in Gary, Indiana, were ready for their moment in the sun and quickly turned their attention to what, exactly, was happening in America’s bedrooms. Their first study was released last month in the Journal of Leisure, which sounds like a fun journal to contribute to, and reports on how the sex lives of almost 2,000 respondents have changed since the onset of the pandemic. The news from the bedroom? Not great. They reported that more “participants said their sex lives declined rather than improved—and while incorporating new activities into one’s sex life was linked to improvements, new additions did not eliminate declines.” So much for a baby boom.

That is, except for a small cohort, less than 15% of respondents, that reported enjoying a higher frequency of afternoon delight than in the year leading up to the pandemic. On further analysis of the data, Dr. Justin Lehmiller, a social psychologist and one of the original study’s authors, found that buttering the biscuit more frequently correlated neatly with political affiliation. On analyzing the data, he found that “liberals were significantly more likely than conservatives to report a decline in their sex lives since the start of the pandemic. They reported less desire for sex in general, a lower frequency of sex with a partner, and a lower likelihood of experimenting with new sexual activities at the time when most of the country was locked down.” It seems that conservatives are knocking boots like the world isn’t ending.

The easiest interpretation of this data is that stress is having a dampening effect on people’s desires to get in between the sheets - but the boost in conservative tush tapping is counterintuitive, given previous research that suggests conservative political affiliation correlates with pathogen sensitivity. Including the right-wing perception of the pandemic as a big ‘ol scam whose sole purpose is to steal the election, this finding is clarified - pathogen sensitivity can’t be triggered if someone thinks it doesn’t exist. Lower perceived risk among conservatives, then, can explain why they’re undeterred in going at it. But the strangeness of the findings goes even deeper.

In addition to feeding the kitty more often, research also seems to show that conservatives lead more satisfying sex lives in general. But why would this be? How is it that, in a world where teenagers raised in post-sexual revolution urban environments, surrounded by acceptance of their newfound sexual identities, conservatives are having better sex?

It may be that at least some of these differences come down to the different living conditions between the two groups. In much of the world, including the US, political affiliation has been shown to track neatly with urbanization. Writing for the Washington Post, Dr. Rahsaan Maxwell, professor of political science at UNC Chapel Hill points out that long-term “Macroeconomic trends have concentrated better-educated professionals in big cities… while agriculture and manufacturing have declined in small towns and rural areas.” As the better-educated have fled towards the cities, they have led to localized increases in density, and have left a wide-open countryside in the hands of the conservatives that are more than happy to take advantage of it.

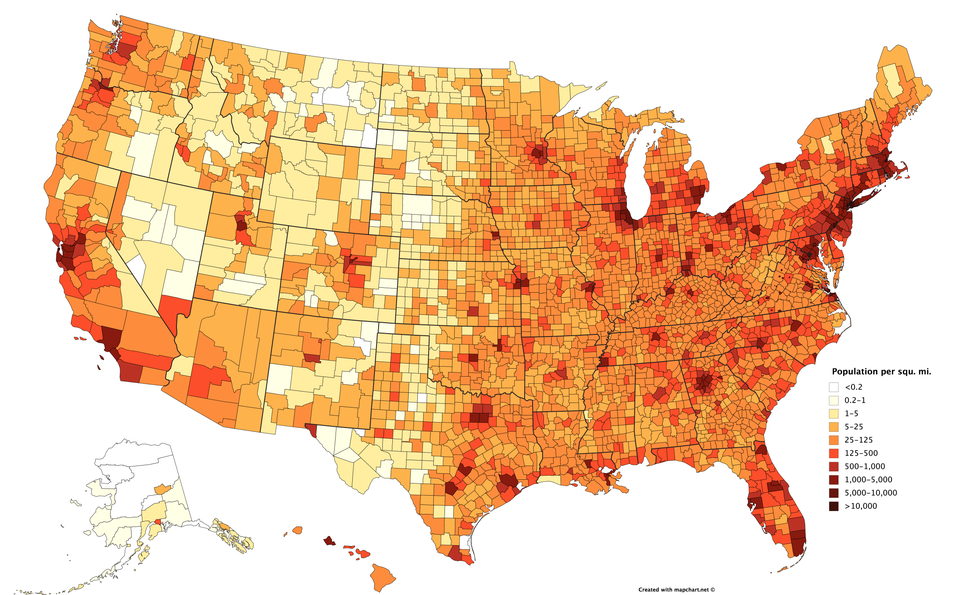

Map of population density by county. Darker colors indicate larger metropolitan areas.

The top graph shows that high-density areas are concentrated around major metropolitan areas, with open countryside between them. The bottom graphic represents the distribution of political affiliation, measured by county during the last forty years of US presidential elections. The overlap isn’t perfect, but the trends are there. Blue districts are clustered around urban centers, and red goes to the countryside. The explanation for the more satisfying sex lives of conservatives might have more to do with this population distribution than we realize.

A collection of US election results, 1988 onwards. Outside of urban areas, the country is overwhelmingly Republican. A great argument against a two party system, too.

On the Rat Farm

Back in the 1950s, an animal behaviorist, John Calhoun, did a series of experiments designed to shed light on how crowding affects the mental state of social animals. The titles of the papers he published on the subject, Ecological Factors in the Development of Behavioral Anomalies, Population Density and Social Pathology, and, my favorite, Death Squared: The Growth and Demise of a Mouse Population, suggest that his results were not encouraging. He examined the behavioral patterns of both mice and rats and felt strongly that they were representative of patterns of human behavior. He started his work almost three decades ahead of the ecology movement, but was motivated by a powerful fear of overpopulation. In the opening paragraph of his last paper on the subject, Death Squared, Calhoun says that he will “speak largely of mice,” but his thoughts are “on man, on healing, on life and its evolution.”

His experiments varied in their details but followed an archetype. He would start by building a room, and then seeding it with several pregnant females. Then he’d sit back and watch what happened, recording diligently what he saw along the way. The rodents would quickly reproduce to a level that was far beyond the comfortable capacity of the habitat - in the Population Density and Social Anomalies the rooms were designed for 80, but the population stabilized at just shy of 1,400.

Over the course of sixteen months, Calhoun found that his experimental rats appeared to undergo widespread psychological breakdown, precipitated by the development of what he termed a “behavioral sink,” a condition where a positively reinforced behavior spirals out of control and results in negative consequences that affect all levels of the society.

In the experimental case, the behavioral sink didn’t happen accidentally. Calhoun, like the malevolent god he was playing, designed the experiment to maximize the likelihood of the development of a sink. He realized that the greatest problem with density was that normal behaviors would get interrupted due to inescapable social interaction, and so instead of using open-topped hoppers with powdered food, he designed large, circular containers where kibble was held back by a metal mesh. This meant rats had to spend slightly more time at the feeder in order to get enough food, and so would often feed with at least one other rat nearby.

The positive stimulus of eating releases dopamine, which created a reward-based conditioning cycle where the presence of other rats was tied to the pleasure derived from eating. Over time, the rats propagated this preference to such a degree that they simply would not eat if it wasn’t in the presence of other rats. This resulted in a spiraling effect, where 80% of all food consumption took place at a single hopper, amidst a social density that was far beyond the 12-13 group size that Calhoun had observed the rats preferred.

Over the course of many months, animals exposed to the behavioral sink displayed signs of an elevated stress response. Female rats had trouble carrying fetuses to term, and experienced severe complications during pregnancy, developed malformed uterine structures, and eventually abandoned nest-building entirely. Infant mortality rose to 96%, and female mortality outpaced that of the males by nearly 4:1. Male rats did not escape the destructive effects of the sink, but their dysfunction was harder to classify.

At this point, Calhoun leaned heavily on his past ethological experience in order to evaluate what a deviation from “normal” looked like. Calhoun binned the males into four different categories, all dysfunctional in their own right. The least abnormal males underwent continuous violent struggles for dominance and displayed periodic aggression where they would attack anyone in sight. Then there were the somnambulists, monk-like recluses who retreated from the social sphere, only emerging to eat and drink while the rest of the rats were asleep. Another group were the pansexuals, who broadened their sexual horizons to include everyone - males, females, and juveniles alike. The last group, the probers, were aggressively sexual, pursuing the females in groups, chasing them into their nest, abandoning all pretense of mating rituals save for the very act of procreation itself.

The results of the rat utopia experiments tugged on Calhoun’s psyche for the rest of his life. He experimented for another decade, consistently recapitulating the uneasy results of the early trials. In the endnotes of Death Squared, one of his last papers, he suggests that “density per se was not the major factor, that rate and quality of social interaction were paramount issues.” Because of this, he felt strongly that humans could rely on what he called their “conceptual space” to cushion the psychological impact of being part of a constantly growing population. But he was certain that humans would soon approach the limit of their ability to keep the crowd at bay. In the closing paragraph of the same paper, he writes that “of opportunities for role fulfillment fall far short of the demand by those capable of filling roles, and having expectancies to do so, only violence and disruption of social organization can follow.”

Many researchers attempted to follow in Calhoun’s footsteps, to recreate the experiments, but they never mapped cleanly onto human society anywhere except for the prison system. For this reason, Calhoun was largely forgotten, a figure that had painted an uneasy vision of what the future might look like. While it’s certain that increased density has not resulted in the collapse of civil society, there are many signs that something is amiss in the cities - the unsatisfying sex lives of liberals may just be the tip of the iceberg.

A recent report, lead by Dr. Jean Twenge of San Diego State University, found that the amount of sex young men between the ages of 18-24 were having in 2018 had gone down by a third since 2000. A study just released by a group at the University of Washington pointed out that global fertility rates were diving precipitously around the world - with places like Thailand and Spain expected to see a 50% drop in population by 2100. In another study, it was suggested that adults born after 1990 were having sex six times a year less than the cohort born during the 1930s.

Scientists don’t have a good sense for why these changes are happening - but few of them are looking into past experience to find inspiration. Dr. Lehmiller, who was only tangentially familiar with the Rat Utopia studies, reiterates that understanding cause and effect “is complex and multifactorial. That's one of the things that makes studying human sexuality difficult and challenging is that there's never a simple search for any of these questions.” But perhaps by looking at all the cards on the table, and what we know about animal behavior, we can start to get a sense of what living in cities is doing to us.