The Mystery of Female Pleasure

Back in 2014, sex researchers from the Kinsey research published some statistics about orgasm, taken from a survey of nearly 3,000 people. When they compared the rates at which single women and men orgasm during a sexual encounter, they found big differences. Men had an 85% likelihood of making it to the finish line, straight or gay, but less than a third of straight women - 60% - were ringing the bell. Lesbians fared a little better, tapping in at 74%, but still lagged behind the stallions.

Though the findings were alarming in terms of gender parity, they were bolstered by other studies that recapitulated the effect and triggered a renewed attempt to explain the mystery of the female orgasm. The prevalence of male orgasm relative to female orgasm makes sense in an evolutionary framework since it’s requisite for reproduction. Without it, none of us would be here, and the world would still be ruled by unicellular bloblobs, exchanging DNA directly without any thought for buildup and crescendo.

Female orgasm, on the other hand, puzzles scientists because the selection pressure for it is much less obvious - especially if you consider the fact that many women report sexual pleasure does not depend on frequency of orgasm. This makes it a biological phenomenon without a clear purpose - an orphan idea that evolutionary scientists don’t take to very easily. In light of this bewilderment, evolutionary biologists and sex therapists have spent a lot of time trying to explain the evolution of the female orgasm.

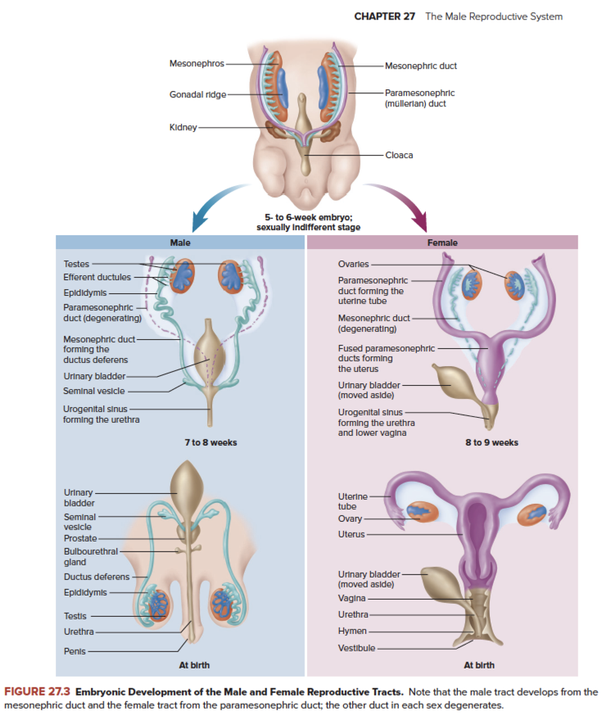

Recently, Dr. Elisabeth A. Lloyd proposed the theory of developmental holdover. In other words, it’s just there for the fun of it. Her rationale is based on the universal body plan that we all start out with, something that’s squarely between male and female. Sex differentiation begins when the fetus starts to produce testosterone and is concluded somewhere around 6-8 weeks into development. This image, taken from Quora but looks a lot like it originated in the Cambell biology textbook, shows the embryogenic dance that occurs in males versus females.

In the middle of the page is a snapshot of differentiation, with a disappearing duct represented in dashed lines on both sides of the equation. The males lose the structure that becomes the uterus, and the women lose the structures that become the vas deferens. Looking at this illustration I wonder if testes and ovaries could be related to kidneys, but that’s for another day.

The point here that the internal, reproductive anatomy is fundamentally similar between the genders, and supports Dr. Lloyd’s hypothesis that the purely-for-pleasure aspects of the female anatomy are holdovers from an earlier developmental time. A glance at the other anatomy - the vulva, the glans penis, the frenulum, the clitoris - it’s apparent that there’s a pervasive overlap throughout the two organs. This figure (NSFW) illustrates external anatomical differences with color-coded structures. It’s worth checking out, if only to see the deep-seated similarities between the two sexes. In Lloyd’s view, the only reason there is a female orgasm is because evolutionary time simply hasn’t erased it yet.

Others, like Dr. John Alcock (né! What a world.), suggest that there’s no possible way the phenomenon isn’t adaptational. Perhaps, he proposes, it is a method for evaluating the potential quality of a mate in terms of genetic fitness and suitability for fatherhood? If that were the case, you wouldn’t expect a woman to orgasm every time during intercourse - but it would still be maintained as an adaptive phenomenon.

Then there’s Dr. Sarah Blaffer Hrdy’s primate hypothesis, which depends on a connection between the behavior of several different primate species - langur monkeys, macaques, and chimpanzees - to humans. She suggests that orgasm is a mechanism for women to protect themselves from depredation. Male monkeys tend towards being a serious danger to offspring that isn’t theirs - but male langur monkeys won’t kill babies of the females they’ve had sex with. She combines this with the observation that chimpanzees will keep having sex until they reach sexual satisfaction, and suggests that orgasm could be a way for human females to ensure a similar degree of protection to their children.

The Missing O

The truth of the matter is that we still don’t know where the female orgasm comes from, and any story that we construct to explain it will be just that - a story. Evolutionary proposals are great fun, but it’s important to remember that it isn’t reasonable to directly compare extant species with one another. They’re different species that have followed discrete evolutionary paths to end up in their present configuration, and interspecific comparisons project a false confidence in the biological overlap between them. What we do know is that sex is a central concern of our culture and our species, and people are having a hard time with it.

Consensus about the causes of the orgasm gap is hard to come by, but there seems to be some agreement about the fact the female sexual pleasure requires more knowledge than male sexual pleasure. In the same way that you don’t need to learn how to breathe (required for survival) but need to learn to walk (technically optional), it may be that female pleasure is something that needs to be learned and perfected rather than being left on the back burner of “I’ll figure it out.”

Dr. Teri Conley, a social psychologist that has been studying and teaching sex for the last two decades, has recently shifted her focus from the science of monogamy to understanding the orgasm gap. One possibility for why it’s so difficult for women to get some satisfaction, in her eyes, is problems with communication. Statistically speaking, “cunnilingus is the most likely path to orgasm, but it’s less frequently present in heterosexual relationships” - especially in hookups. This isn’t just because men are sometimes less-than-enthusiastic about it - she’s found that women “might not want to have cunnilingus performed because of self-esteem issues, such as thinking that their bodies are gross or undesirable.” This creates a feedback loop where men have less opportunity to learn, and women don’t learn to enjoy themselves.

But even in a situation where a woman is comfortable with cunnilingus, and is with a man who is good at it, “even in this best-case scenario - to him how fast or how slow to go, changes in pressure she wants, to use more lips or tongue or teeth. And she has to be able to that in such a way that it doesn’t interrupt the likelihood of orgasm, which usually requires a specific set of motions and pressures.” With communication breakdowns effectively preventing feedback from being integrated, it’s no surprise that so many women are finding their satisfaction falls down the wayside.

When the world is collapsing under the weight of economic inequality and racial unrest it can seem like a downright frivolous pursuit, this female orgasm business - but there has been plenty of research that shows orgasm has an uplifting effect on overall health and a positive effect on mental health. But with fertility rates across the world decreasing, falling sexual frequencies, and the aforementioned orgasm gap, it seems like the entire world could use a little more satisfaction in their bump and grind to go with the other, daily, grind.

Sex researchers for decades have been trying to understand the underlying issues that lead 10-15% of women to lifelong anorgasmia, as well as 40% of women experiencing some kind of inability to reach orgasm in the past year, but have largely failed to produce crackerjack results that can account for the myriad of issues - physical and psychological - that can lead to a life that lacks satisfaction. Luckily, we live in an era where disruptive technologies are dedicated to helping us close the gap.

Artificial Intelligence of Desire

About a decade ago, Lioness CEO Liz Klinger found herself out in the Connecticut sticks, a graduate of Wellesley College with a degree in art and a smoldering interest in human sexuality. She looked around and quickly realized that, without graduate school, her career options in the field were limited to commuting into NYC to work at a progressive sex shop like Babeland - or to host passion parties, “the Tupperware sales of the sex toy world.” Hawking her wares allowed her to run the gamut of female spaces - from sorority houses to retirement parties - where she found that women had similar questions about desire, pleasure, and the strange things their bodies did. In all of these spaces, the question of sexual satisfaction was front and center - but she didn’t have much she could offer these women.

Rather than just shrugging her shoulders and sending them off with whatever new toy was in her arsenal, Klinger was galvanized into action. “I wanted to build something that could help people with their sex lives in some way,” she reminisced during a recent interview. “So James and I teamed up with a couple other people and iterated on different ideas. At the end of the day, we had come up with a device that could help users reach orgasm.”

In the basement of UC Berkeley, Klinger, Wang, and chief engineer Anna Lee used their shoestring budget to produce Generation zero of the Lioness - a smart sex toy that came equipped with four sensors - temperature, motion, acceleration, and pressure. The “beta test device was this whole mess of wires, with a hard connection. We had to physically send it to our beta testers, who used it and sent it back.” The team downloaded the data, analyzed it, and then uploaded a PDF of the session for the pioneering couple. Though generation zero was a far cry from the sleek, silicone toy that it is today, the results were immediate.

“When I got them on the phone the wife was like ‘holy crap, we finally were able to talk about these things that I’ve had a lot of trouble talking about.’ It turned out that she wanted more foreplay, and he didn’t know quite that that meant. He’d spend more time but it just didn’t match up, you know?” But with a chart of sexual arousal over time in hand, Klinger found that they could have a conversation “without the subtext of ‘oh, you’re not good enough, or I don’t like you enough,’ on the husband’s part and ‘I’m so tired of talking about this’ on the wife’s part. Having the chart in hand can change people’s perceptions of their own experiences, and how they talk about them with others.”

The final prototype of the toy, Lioness 1.0, contained a core set of tools - four sensors, and a phone app. The force sensors are the “star of the show,” says Klinger. They’re the parts of the device that have helped Lioness produce a library of over 50,000 orgasms - the most complete representation of female pleasure that the western world has produced up until this point.

After each session with the toy, the app produces a graph that shows the contractile force of the pelvic floor muscles. The pattern of contractions accelerates during orgasm, and is used to create a model for what orgasm looks like physiologically, and allows users to compare their orgasms under different conditions. One woman found that after she experienced a moderate concussion, her orgasms all but vanished. Another group of women started an orgasm book club, comparing charts, tips, and tricks. A third found that THC-infused lubricant gave her longer and stronger orgasms (seriously worth following up on that one…).

Across the board, it seems like Lioness has achieved its first goal of helping women find their way to orgasm. Having everything laid out on a chart helps women who are struggling with the orgasm gap communicate more clearly with their partners, and helps people who are playing on their own to figure out what it is their body likes. The next stage? Not quite taking over the world, but changing our perspectives on the necessary role of pleasure in a long and healthy life.

Changing Minds, One Booth at a Time

Over the course of the last decade, Lioness has seen public perception of the company change significantly. Back in the early days when they just started out, they applied for an account at Silicon Valley Bank, a financial institution that was seen as a vital networking opportunity for just-off-the-ground startups. On their third attempt at opening an account, Klinger says they made some headway by appealing to a few of the senior directors that were in the healthcare space. They pitched Lioness as a way to improve women’s health, rather than a prurient novelty product and got an invitation for an in-person meeting at bank headquarters in Palo Alto. But when they got there, an associate took them to a side-room near the entrance and apologized - people were talking, and the bank just couldn’t afford to get its name dirty. They left.

The bank incident was just the tip of the iceberg. Last year, at a women’s health tech conference, Klinger set up their booth only to hear from a third party that they had to put the vibe away - it didn’t belong. Klinger was astonished since the conference was “for women's health and we were talking about the nerdy, medical side of things - not just selling a vibrator. I had a weird back and forth through the third party for, like, four hours.” By that point, the conference had wound down, with the toy out of sight for the entire duration.

When Klinger finally got to speak with the woman who had decided to pull the Lioness at the last minute, it turned out at first that she didn’t think sex toys had anything to do with women’s health. Once Klinger presented her with information to the contrary, she pivoted to it not being a “wearable.” The just-so nature of the woman’s justification brings to mind Jonathan Haidt’s experience with post-factum moral justification. When confronted with an action, good, or service that triggers their moral reasoning, people will create any number of knee-jerk justifications by which to condemn whatever has caused offense.

“It’s almost as if their moral aesthetics are offended,” muses Dr. Conley, when asked about the mental gymnastics of sex research opponents. “It’s an immediate response, it doesn’t look good, it doesn’t feel good to me. Often this is part of a slippery slope argument,” a logical pedigree that contains such gems as “if you let men marry each other, they’ll want to marry their dogs, next.”

Klinger is quick to point out that, just last year, Silicon Valley Bank reached out to see if they still wanted to open an account. The way had been paved by Hims and Rowan, a new generation of erectile dysfunction pills, but Lioness hasn’t moved over quite yet. “It’s just not a priority right now,” she confessed. Samsung has since apologized for the wearables debacle, but there’s been little progress on getting the Lioness in front of people.

Unlike in the cannabis and psilocybin space, where there’s a push to legalize something that was previously outside the law, there’s no such switch to turn here. “Issues related to sex are in this gray area where there’s an unwritten rule. There’s just someone in the hierarchy who just… isn’t okay with it,” she sighs. Even when they do get a positive response from a member of the ad team, “some of these companies are so big that there's no one person who has the decision to turn the switch.”

Generation 2.0 - Citizen Science of Sex

Lioness has been a unique sex toy since Klinger, Wang, and Lee connected the first wires back in the early 2010s, but this year they’re striking out for new territory - a collaborative research platform with scientists interested in studying sex in the wild. The toy, with its four sensors, is a perfect candidate for the kind of hands-on sex research that institutional review boards are well-known to get squeamish about.

Bolstered by an overwhelmingly positive response from their data-loving user base, Lioness is once more into the unknown. Unlike Lovesense and We-Vibe, smart sex toy companies who were surreptitiously recording and storing data, Lioness has the enthusiastic consent of its users. Soon, users will be able to opt into a variety of research projects, organized and executed by researchers interested in the many facets of female sexual pleasure. Users will be able to choose what surveys they participate in and what data they share - they’ll even be able to opt-out completely.

Threading the research needle might be the step that helps Lioness make it into the mainstream. Conversations with healthcare accelerators in the Bay Area have convinced Klinger that “the healthcare industry is interested in getting something pleasure-oriented into the hospital because doctors often work with patients who have conditions that affect pleasure. This would be an easy way to improve their quality of life,” and help science better understand women’s sexuality in the process.

More than anything, though, Klinger is an exception to the typical Silicon Valley tech CEO in her focus on ethics. She’s got two lofty goals. The first is to “build this company and the subject matter into something credible, that’s treated with respect.” The second is informed by her own experience of growing up with an eating disorder, deeply preoccupied with the other. “We've made enough decisions and with our company that it’s clear we’re not just purely seeking profit,” she laughs.

Wherever the research platform takes them, it’s going to be centered on “building a good community and a product that is able to help people. Rather than just throwing paint to canvas and seeing what happens, we want to build this out in a thoughtful way. It’s an interesting balance because there's all sorts of things that we could do. But I spend a lot of time thinking about the consequences of what happens when share information in ways that may not be that accurate to life. I don’t know why I’m like this!” She shrugs and smiles, suggesting it doesn’t bother her too much. “Maybe it’s because of my personal experience with anorexia. I don’t want that experience on my platform.”